OCTOBER 18, 2017 11:00 AM

http://www.kansascity.com/news/politics-government/article179485646.html

It’s no secret that state government in Kansas is smaller than it used to be.

But you might be surprised at how much smaller.

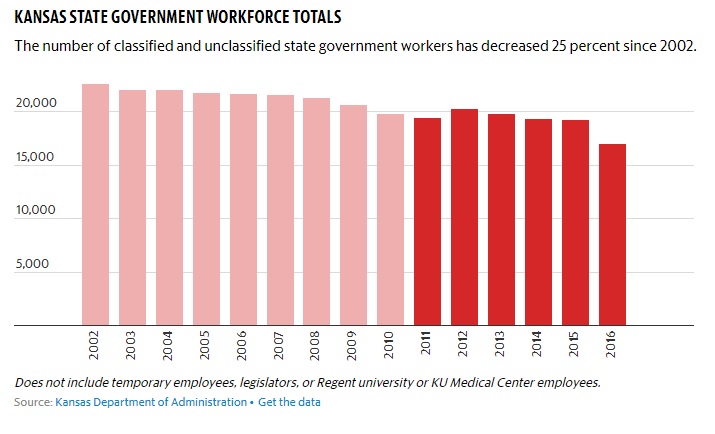

A review of workforce reports reveals that the number of non-university state employees shrunk about 25 percent between 2002 and 2016.

Fewer state social workers to handle vulnerable adult and child welfare cases. Fewer guards to secure prisons. Fewer troopers and highway patrol staff to keep highways safe. Fewer medical professionals to care for the mentally ill in state hospitals.

“The image people have is a faceless bureaucrat pushing paperwork, but in reality it’s public safety… that’s where the real effect of these policies and political talking points has come home to roost,” said Rep. Melissa Rooker, a Fairway Republican.

“Those were not all excess positions to cut away the fat.”

While Gov. Sam Brownback is notorious for trickle-down style tax cuts — which have since been reversed by the Legislature — it’s the government workforce reduction that could have an even bigger impact on Kansans for years to come.

The reductions didn’t start with Brownback. In the eight years under Democratic Govs. Kathleen Sebelius and Mark Parkinson, whose terms were bookended by the post-9/11 recession and the Great Recession, the non-university state government workforce decreased 12 percent.

During Brownback’s shorter six-year tenure, the number of state government workers decreased 14 percent.

Now, Brownback is preparing to leave Kansas for a new job in the Trump administration as the U.S. ambassador at large for religious liberty, a State Department post based in Washington. He’s already gone before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and needs approval by the committee and then 51 senators for the nomination to be confirmed.

That leaves the Legislature and the future governor, Lt. Gov. Jeff Colyer, to decide how to move forward.

“We’ve got a lot of damage to repair,” Rooker said. “It will take a decade to recover from this combination of budget cuts, austerity measures and changes made within agencies.”

Lost institutional knowledge. High turnover. Fewer people holding the keys to power and information.

“Not only have we depleted our workforce in terms of numbers, but we’ve also depleted it in terms of expertise, which is why so many of our agencies are underperforming,” said Sen. Laura Kelly, a Topeka Democrat.

Last year, there were just over 17,000 non-university employees in state government — a loss of more than 5,600 workers since 2002, according to data from the Kansas Department of Administration workforce personnel reports.

Nearly every state agency has seen reductions — through reorganization, privatization, cuts, attrition, unsuccessful recruiting or a combination of those things — in the last 15 years.

A Star analysis found the agencies most affected from 2002 to 2016:

▪ Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services, now called the Department for Children and Families, has lost nearly 1,800 employees (49 percent)

▪ Department of Transportation has lost more than 1,050 employees (34 percent)

▪ Highway Patrol has lost 117 employees (14 percent)

▪ Adult correctional facilities (El Dorado, Ellsworth, Hutchinson, Lansing, Larned, Norton, Topeka and Winfield) have lost 539 employees (nearly 20 percent)

▪ State hospitals (Larned, Osawatomie, Parsons and the Kansas Neurological Institute) have lost more than 534 employees (25 percent)

‘Intentional effort to downsize’

Nationwide, the number of non-university state government workers was fairly stagnant in years leading up to the Great Recession, between 2002 and 2006.

After the recession, the number of state workers nationwide started to decline, but not as drastically as in Kansas, according to an analysis of federal data by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research institute based in Washington, D.C.

The reason? A combination of the recession and states not wanting to raise more revenue through taxes as soon as things turned around.

“The Great Recession had a dramatic and very immediate impact, so there were decisions that had to be made and that was several rounds of straight up, ‘We’ve got to cut X percent across the board,’ ” Rooker said. “What we should have done coming out of the recession is invested. We started to recover and that’s when you had a new administration come in that decided to double down and continue the process of cutting.”

In a statement, Brownback said his “approach has always been that state government should have fewer, but much better paid employees. With that in mind, I’ve directed targeted pay increases for social workers, corrections and Highway Patrol officers. I also worked with cabinet secretaries to make the pay plan approved by the legislature this spring more fair and equitable for our state workers.”

Part of the reductions were purposeful and part of the Brownback administration’s philosophy of smaller government, said Shawn Sullivan, state budget director.

“In some agencies, particularly those in general government, there’s been an intentional effort to downsize, to be more efficient,” Sullivan said. “As staff left or retired, internally we would check to see if we needed to replace them with someone else, combine positions with another at that agency.

“In other places like (state) hospitals, we’ve had reductions, but I wish we wouldn’t have.”

For example, Larned State Hospital and Osawatomie have both seen about 30 percent staff reductions, according to state data. Sullivan said it has been difficult to recruit, particularly in western Kansas, and that the administration is working on things like increasing pay.

“There have been certain cases where we have struggled with revenue in the last couple of years that agencies have looked for further efficiencies so they will be able to keep the impact on their programs minimal,” Sullivan said.

Started with Sebelius

Like now, when Sebelius took office in 2002 the state also had an unresolved school finance case and some priorities that were not going to be fully met.

“We really started with a hiring freeze mentally, not deliberately eliminating things,” Sebelius said. “Then we did a broadbase look at efficiencies in state government.”

One of the biggest cuts was to the Department of Administration, which shrunk by 268 employees, or 35 percent, from 2002 to 2009, according to state data. Another was the Department of Labor, which was nearly halved from 822 to 421 during that time.

Sebelius said her administration froze vacancies after review, sold cars sitting idle, inventoried buildings and focused more on agencies that did not deliver human services. New technology also played a role in consolidation and replacing vacant positions with updated technology.

“At the outset, some things were off the table, anything with services to vulnerable populations,” Sebelius said. “We knew that was a lousy way to save money, it makes prisons less safe and puts foster kids in jeopardy.”

‘Experienced manpower’ lost

Lately, one of the biggest issues is staffing within the Department of Corrections, said Sen. Carolyn McGinn, a Sedgwick Republican and chairwoman of the Senate Ways and Means committee.

“We don’t have enough people to work a proper working day, especially in an environment that people need to be rested and alert, so now we have people that are working 12-plus hours a day,” she said.

“In the end, it causes safety issues for the people that work there and it can cause safety issues for people who are supposed to be seeing a parole officer on work release.”

Over the summer, amid inmate disturbances, the staffing shortage increased at Kansas’ largest prison in Lansing. At one point in July, Lansing Correctional Facility had 116 staff vacancies. The Kansas Department of Corrections says the facility, which houses more than 2,000 inmates, needs a staff of around 682 workers.

Another state prison, El Dorado, also dealt with staff vacancies, and in late June, some inmates refused for several hours to go back to their cell blocks. The workers union filed a complaint in July and said some employees at El Dorado were being forced to work 16-hour shifts. In August, Brownback approved pay increases for prison workers.

McGinn said her constituents have also called her to complain about seeking services from the Department for Children and Families.

“They can’t find anyone to talk to locally,” she said. “It used to be that we had regional offices and case workers that would help people get connected and get through bureaucracy in Topeka. Now that doesn’t happen.

“I do believe part of (the problem) is manpower, and more importantly lately it’s experienced manpower — people with knowledge and history of how to get those pieces connected.”

DCF figures show the number of full-time social workers handling child welfare and vulnerable adult cases has decreased 15 percent since 2010. Meanwhile, in the same time frame, the number of children in Kansas foster care has increased about 40 percent.

During Brownback’s administration, membership in the Kansas Organization of State Employees has gone from about 12,000 to 7,500, union president Robert Choromanski said.

“Veteran state employees are leaving in droves across all state agencies,” he said.

Part of the reason is double-digit increases in some health care premiums, the state pension program not being adequately funded, and wages not keeping up with inflation. Some state employees have decided to give up their civil service protection classification in order to get a raise, he said.

‘A healthy path’

McGinn wants the Legislature to immediately focus on agency staffing when it reconvenes in January.

“We need assessments of individual agencies or audits to find out whether we’re meeting the needs of folks,” McGinn said. “I don’t think it’s a matter of we need to hire X amount of people. We need to do measurements within every agency and ask if we’re doing the job that Kansans have asked for, particularly with our seniors and disabled.”

Sullivan, the budget director, said he welcomes legislative oversight.

“We often hear legislators say that we’ve cut to the bare bone in staff,” Sullivan said. “I challenge everyone to look at the outcomes of those agencies.”

Staffing levels can’t be increased overnight, and likely won’t be for years. Those decisions will fall on the shoulders of a new governor and the Legislature.

The entire House of Representatives is up for re-election in 2018.

“We have a whole lot more work to do to get things back on a healthy path…,” Rooker said. “It’s been evident for awhile and it played an outcome in the 2016 elections. I think people are feeling it in their daily lives, in one way or another.”

Kelsey Ryan: 816-234-4852, @kelsey_ryan